a million of music

My body speaks, my lips repeat

pure Ihy-music for Hethert.

Music, millions

and hundreds and thousands of it,

Because You love music,

a million of music for Your ka,

In all Your places.

~ King Antef (source: Hathor Rising, A. Roberts)

Personal conjecture: Ihy is Hethert’s (Hathor’s) son, Whose name reflects the jubilation of musical instruments in the sound they produce and in the act of playing them. “Ihy-music” in this may indicate both Ihy, Whose music soothes and pleases His mother, and also, more generally, ecstatic music.

PBP Fridays: M is for Marking the Days

I always thought of Summer Solstice as a Wiccan thing (when I was young), or an eclectic-pagan thing (when I was slightly older). I didn’t think it would follow me home to Kemeticism.

But here it is, a radiant drop of sunlight in the form of a lioness, the Wandering Goddess come home to Kemet at the peak of the daylit year.

As part of writing about Anhur, I summarized the Myth of the Distant Goddess:

The myth, in short, tells the tale of the Eye of Ra becoming angry and leaving Kemet (Egypt) to go away, often to Nubia. The reason that the Eye goddess becomes angry can vary, but a frequent version of the myth tells how Ra sends his Eye to search for Shu and Tefnut, Who have gone off wandering in the world that is not yet done being created; when the Eye finds Them and returns Them to Ra, She finds that Ra has grown another Eye in Her absence. Angry with Her replacement, She storms off and wanders the desert, hostile and disconsolate.

In order to regain His protection under the Eye goddess, Ra sends a hunter-seeker to find Her and persuade Her to return. Depending on the version, the god Ra sends accomplishes this feat by a mixture of cajoling, praise, promises of riches and joys upon Her return, and reminders of the Eye’s duty to Her father. When the Eye comes back to civilized lands, She is met with rejoicing, offerings, and festivities by the people of Kemet.

Different gods can play the roles of the Eye and the seeker in this myth. Often, it’s Shu who is sent to bring His sister-consort Tefnut back; other times, it’s Djehuty in His baboon form that teases and flatters an Eye goddess like Hethert (Hathor) or Tefnut until She agrees to return. However, Anhur Himself is often the hunter Who finds, and the Eye Whom He brings back is Mekhit/Mehit/Menhit, the lioness Who then becomes His consort and wife.

Today, the Summer Solstice, is the Feast of Hethert, Eye of Ra—today we celebrate the Lady of Gold’s return to Kemet in the longest day of the year. Today is the joyous peak of the year’s wheel, the explosion of life and heat and light that shines in glory of Hethert’s return to us.

The beauty of your face

Glitters when you rise,

O come in peace.

One is drunk

At your beautiful face,

O Gold, Hathor.

~ inscription from a tomb at Thebes (source: Hathor Rising, A. Roberts)

Welcome home, Hethert, Mistress of Heaven! You bless the world with Your smile and the warmth You bring. Dua Hethert, Gracious One!

Last year’s first M post was a Monstrous Manifesto.

Treading the Fishes

I took a bit of catfish from my partner’s dinner plate and squirreled it away with a piece of crabcake from my own meal, wrapping them both in a napkin and tucking it into my shirt pocket. When he didn’t bat an eye or remark on my seafood hoarding, I laughed. “It’s for Treading the Fishes,” I told him, and he made the ohhh of recognition. For a non-Kemetic, he’s pretty savvy.

Treading the Fishes is a multi-day festival that celebrates recurring fertility and kingship; lasting from III Shomu 19 (Monday) to III Shomu 23 (Friday), it involves the king treading on dried fish, hence the name. Stomping the fish is symbolic of conquering isfet (uncreation), but also ties into the cyclical fertility of the land, as the fish are buried to provide nutrients to the soil for the next growing season. The king would also re-dedicate herself to her nation of Kemet and offer the Heqa sceptor, a symbol of rulership, to Khnum, the Netjeru Who makes the each human on His potter’s wheel.

So I took my tiny bit of fishes out to our little garden-like section near the front door and dug a shallow pit, then tucked the food, now wrapped inside a folded paper, into the soil. I covered the packet with fresh dirt, watered it with pure water (to help the paper start decomposing), and gave it a good couple stomps; I am certainly no king or representative of one, but I am happy to participate in symbolically refertilizing the earth and helping ensure the next good growing season. The act of setting aside some bounty to fuel and welcome the next surge of abundance feels very important to me, not to mention useful and applicable in many different areas of life.

On the paper that held the now-dried fish, I had written a little heka:

As the land provides for me,

so I provide for the land in what ways I can;

as Netjer provides for me,

so I offer to Netjer in what ways I can.

I give back part of what I receive

to open the way for abundance.

Dua Wesir and Set, Who dance the cycle

of green growth and fallow rest,

both equal in the eyes of Ma’at!

Dua Geb, Who encompasses both crest and trough,

Who makes us mortals live with His gifts!

PBP Fridays: L is for Lions

I don’t really like lions. This is hilarious for two reasons and understandable for the third:

1) I draw some hefty parallels between the behavior and physiology of the extinct-in-the-wild Barbary/Atlas lion and myself. I don’t consider the Barbary lion to be totemic—it’s not an external entity to me—but I do find it to be a disconcertingly accurate mirror into my own instincts, intuition, internalized sense of self, and social patterns (or lack thereof). If you stuffed a baby Barbary lion into a human suit and raised it as a person, it might turn out a lot like I have. This is both a sorta-cool thing and a frequent disadvantage in normal human life. :)

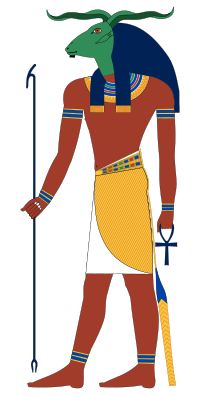

2) Two of my gods, Sekhmet and Ma’ahes, are leonine deities. I never see either of Them as purely human; They always appear as animal-headed people or full lions, often wreathed in flame (Sekhmet) or magma-skinned (Ma’ahes). The traditional symbolism of the African lion (power, nobility, dominance/lordship, the sun) and African lioness (ferocity, motherhood, the tribe, the sun) is very intense in Them and reflects a large part of Their characters.

3) I freaking love spotted hyenas. African lions are pretty much meh in comparison. I also think they’re kinda over-hyped, and as I am secretly a hipster, I tend to stray away from anything “too” mainstream. I prefer investigating the obscure and exploring the little corners, rather than strolling down the big ole well-trodden pathways.

A large part of the disconnect between me and the African lion is not just thanks to my adoration of hyenas or my elemental-lion impressions from my Netjeru—it’s due to the drastic differences between Barbary lions, with which I identify, and the African lions that everyone’s familiar with. Barbaries weren’t pride animals; they lived alone or in hunting pairs. While males and females were still sexually dimorphic in terms of size and mane, they didn’t serve different social or gender roles; each Barbary still had to hunt, claim and defend territory, and find a mate. And, speaking of territory, Barbaries lived in the Atlas Mountains in northern Africa, where the terrain was, well, mountainous, and the climate was semi-seasonal instead of the hot savanna’s whomping dry-wet cycles.

So the lions I grok are not the lions everyone refers to when they say “lion,” and while I am appreciative of the uniqueness of African lion social structure and other facets of their physiology and behavioral patterns, I just don’t admire and geek out over them like I do other animals like hyenas, scorpions, and snakes. The physical reality of the animal doesn’t win me over, even as I can respect the power that the lion wields in mythology and symbolism. Even with Barbary lions, my reaction is more “welp, that’s me” instead of “HOLY CRAP THEY ROCK.”

That said, I still love lion gods:

Last year’s first L post was on magical language.

KRT: How I Began

This post is part of the Kemetic Round Table, which aims to answer some of the most common questions and provide a wealth of diverse options for the Kemetic novice to explore.

How did you get started in Kemeticism? Tips? Stories?

Tips? Nah. Stories, on the other hand… oh, yes.

Let’s get the non-Kemetic background out of the way: I was raised nominally Christian. My dad is a Roman Catholic, my mom was loosely a Baptist. We didn’t do church, except for once in a while with my dad’s parents. I didn’t grok Jesus but talked to God a little, and when in my zealous ignorance I offended a non-Christian friend as a teenager, I took it upon myself to learn more about non-Christian religions. I studied Wicca, then began practicing Wicca, along with non-denominational energywork and totemism and Otherworld journeying. My mom was in the know and vetted the books I bought. At eighteen, I swore myself into the Goddess’s service and came out to my parents about being pagan (and being queer, because I am an honest sonuva). Over time, my flavor of paganism changed from Wicca to eclectic nature-lovin’ to monolatry (the Divine is both Many and One) to almost-agnostic.

And then, after years of not having any specific god other than brief glimpses of Brigid and Lugh… I met Sekhmet.

To be exact, I called on Her. It was 2005, and I was a social and emotional doormat, and I knew I needed to grow a spine—so I petitioned a lioness goddess with enough Fire to light one under my ass. I had done some cursory digging on potential deity fits, and since I identified so strongly with the lion, a feline god was particularly appealing. So it was Sekhmet I prayed to, and Sekhmet I invoked, and Sekhmet Who answered with Her fierce, no-nonsense strength.

Years passed as I danced around Her flames, orbiting Her intensity like a reckless moon, glittering with the light She threw across me. As our relationship gradually, in fits and starts, deepened and strengthened, She demanded more traditional worship of me. I, the eclectic, the soil-palmed shapeshifter, could not reconcile my spontaneity with the formality and gilded perfection of ancient Egyptian ceremonialism. So we compromised: She would forgive my forms of ritual and worship, and I would at least research, study, and understand ancient Egyptian religion and mythology.

I had been alone in my devotion to my Red Lady, but I did know two other Egyptian pagans. (I didn’t know the word Kemetic back then.) One was a fellow devotee of Sekhmet, and one was a Jackal-child; the latter was a member of Kemetic Orthodoxy, an Egyptologist-led Kemetic temple that seemed to espouse soft reconstructionism. I balked at the idea of socializing with an entire temple in order to learn, bared my teeth at their insistence on “real” information (like name and birth date) in order to join a beginner’s course. I was a lurker who self-taught at my own pace, and the idea of being visible to more than a couple of people at a time unnerved me deeply.

But I promised Her, didn’t I? And the beginner course was no-obligation. So I swallowed my instincts and stepped into the light, flinching all the while. I clung to Sekhmet like a child to the hem of its mother’s dress, and She tolerated my inanity; She had never coddled me. In all our years together, She had defended me fiercely on the rare occasion I needed defending, and She had interceded on my behalf when I bartered a favor for Her to do so, but not once did She give me the impression that She would put up with my bullshit, my whining, and most especially, my rampant insecurity. I had come to love Her with a blinding devotion that I still can’t explain, and I could not forget that She was only in my life at my request, not Her own insistence.

Stepping into Kemetic Orthodoxy was an eye-opener. My nervousness at being visible soon faded to manageable levels, and I felt welcomed by a warm, engaged, smart community. Diversity was welcomed, not just tolerated. People were encouraged to both learn about the Netjeru from historical sources and to experience Them personally, subjectively. The tenets of Kemeticism matched up flawlessly with my own values, and with the worldview I had created and adopted for myself at Sekhmet’s urging years earlier, when we both tired of how many externally-imposed ideas I was trying to make work in my own paradigm.

During the beginner course, all students are encouraged to open themselves to Netjer and not focus on any particular gods. Hah! I did my best, and along the way, I began interacting with a couple of new-to-me deities, including Serqet (Who I prayed to) and Ma’ahes (Who insisted on my attention). I also met Nebt-het, Set, the Jackals (Wepwawet and Yinepu/Anubis), and Twtw. I acquired a hoard of historical books and read some of them, and I practiced integrating pieces of Kemetic ritual, heka, and prayers. Sekhmet was quiet, giving me the space to explore and interact with other Netjeru without being so close that I couldn’t see anyone past Her.

After the beginner course ended, I became a Remetj, a friend of the faith. And I signed up for the Rite of Parent Divination, a geomantic rite of passage that would reveal the Parent(s) of my soul and the Beloved(s) Who watched over me in this lifetime. (Note: This is a modern rite specific to Kemetic Orthodoxy, and it is not required of any Kemetic, nor does it limit which deities a person can interact with or worship.) I was exhilarated, nerve-wracked, and convinced that Sekhmet would not show up in the divination… while simultaneously not-so-secretly wondering if She would appear as my Mother. I swore to Her that, no matter Her place in or outside of that divination, She would not lose Her importance in my life and practice.

She was not there. I was divined a child of Nebt-het and Hethert-Nut, beloved of Ma’ahes and Serqet. I was overjoyed and stunned. And it took me months and months to come to grips with Sekhmet’s absence in my divination, against all odds of logic, my own promise, and the simple fact that the divination is not the be-all end-all of anything. Even as I struggled between intellect and emotion, I created a relationship with my akhu, the blessed dead who are my ancestors, and grew closer to the four Netjeru Who were in my divination.

A little over a year after my divination, I had settled in: with my gods, with my akhu, and with my community. I had proven to myself that I could participate with and bring value to the people I came to admire and enjoy, and that I could devote myself to many gods without enormous conflict. And so I felt I was ready to take Shemsu vows and become a “follower” of Kemetic Orthodoxy, swearing myself to my Netjeru and my community. I received a Kemetic name when I took those vows in February of this year, alongside my sister.

And now? Now, I am committed to my gods and Their people, to upholding ma’at in my life and self, and to maintaining this blog and my physical shrine as devotional works. I am at peace in my religion, with my spirituality; it is a dynamic, living, growing, evolving peace, and I am glad to walk this path.

If you enjoyed this post, please check out the other how-we-got-Kemetic stories by my fellow Round Table bloggers!

PBP Fridays: L is for Logic and Religion

I intend for this to be a beautifully short, straight-forward post.

Logic and religion are not mutually exclusive. In fact, they are best when hand-in-hand, supporting each other. While you can certainly have logic without religion, I would never recommend having religion without logic: it’s a dangerously imbalanced equation.

Logic helps a religionist function as a discerning, responsible person, both individually and within society as a whole. (It also helps them make up cool words like “religionist.”) Logic helps a religionist understand what is objectively factual and what is subjective experience, and logic helps a religionist accept and engage with questions, doubts, and debates in a level-headed, rational manner.

And religion—or spirituality, if you prefer that term—helps logicals remember that there is magic, meaning, and divinity in the world. Religion-slash-spirituality helps logicals survive and thrive in an unpredictable, chaotic, uncanny reality where not everything is, well, logical and sensical. Religion-slash-spirituality helps logicals exist beyond the physical senses and mundane routines so they can touch the numinous and remember that the Universe-sized picture is more than what they can see right now.

Logic and religion are bedfellows, best friends, and PB&J. Science, logic’s bro, is the foundation of some seriously amazing shit (and is the basis of my own spiritual practice); religion-slash-spirituality lends an even deeper, more breath-taking meaning to all of the bedazzling natural phenomena that we learn is measurably real.

Religionists, be logical, savvy, questioning, discerning, rational, responsible people. Logicals, be awe-filled, sensory, questioning, experiential, enthralled, daring people.

Or, better yet, be all of the above. :)

Necessary Disclaimer: Why yes, logicals can be awe-filled without being religious. For the sake of brevity, I have summed up, but I am by no means being exclusionary towards the many non-religious logicals who are absolutely filled with wonder for the world.

Last year’s first L post was on Lugh.

Utterance 260, PT

My refuge is My Eye, My protection is My Eye, My strength is My Eye, My power is My Eye. O southern, northern, western, and eastern gods, honor and fear Me. I go that I might bring justice, for it is with Me, and I will not be given over to the flame.

PBP Fridays: K is for Khnum’s Gift

With ram-horns and ram-eyes and the breath of life,

With ram-horns and ram-eyes and the breath of life,

Khnum sits at His potter’s wheel in Abu,

The Seat of The First Time;

and in that place where the world was born,

He spins His wheel and makes we mortals,

our souls and flesh as clay in His skillful hands.

Into some sweet few, a little piece of Him slips,

a seed and a spark of fragrant inspiration,

and up we rise—up she rises,

and her hands seek out the clay like His do,

and she shapes bodies and hearts like He does,

a small and lovingly-crafted reflection of His work.

Dua Khnum, Who shapes, Who creates!

Dua Khnum, Who breathes into us shining life!

Dua Khnum, Who imbues us with His craft!

For Saryt, my beloved sister and most talented and imaginative sculptor-of-creatures.

KRT: Setting Up A Kemetic Shrine

This post is part of the Kemetic Round Table, which aims to answer some of the most common questions and provide a wealth of diverse options for the Kemetic novice to explore.

Before I begin, I would like to clarify that the information in this post is my personal opinion only; it reflects the influence of Kemetic Orthodoxy’s guidelines and requirements of a shrine, but is more than just those guidelines. Specifically, in terms of purity, Kemetic Orthodoxy does not recommend having any animal products in or on a shrine, including plastics; I do not follow that restriction.

That said, let’s explore what constitutes a Kemetic shrine! For sake of simplicity, I define a shrine as a place for religious worship and activity, including making offerings and prayers. It is not just a static place to showcase icons of Netjeru; it is a place to “work” by actively participating in ritual and dialogue at or with your gods. While statues, images, and other items depicting or symbolizing a particular god can be part of a “working” shrine, the shrine is more than just those sacred objects.

Whenever possible, I recommend having a dedicated shrine space in a relatively private and undisturbed place that doesn’t get extra dirty; a corner of a bedroom or a spacious shelf in a closet will both work, as will a mantleplace shelf or small table set up somewhere things won’t get easily knocked over. However, for many Kemetics—especially those just starting out—it’s not practical or even possible to have an ever-present shrine area. Some low-tech solutions include having a TV tray you can fold out to use as needed, or clearing off a nightstand, or purchasing a cost-effective wooden shelf (even an unpainted one from Michael’s or another craft store) to use for a shrine. It is especially helpful to have an altar cloth if you can’t leave your shrine set up all the time, as the cloth helps distinguish the mundane and the sacred uses of the surface in question and to keep your shrine items clean. White is traditionally a great color for the cloth, but other solid colors or patterns can still work just fine.

There are a few items I would always recommend a “working” shrine feature, and even the most sweetly simplified shrines can benefit from having them:

- an offering plate (for dry offerings, including food)

- an offering cup (for liquid offerings, including pure water)

- a candle (can be an electric candle if you can’t burn a real one)

- a source of scent (an incense burner or oil warmer or potpourri or whatever suits your personal tastes, respiratory needs, and living space constraints)

Beyond those four items, you can include as much or as little as you wish, provided it is sacred to you. I feel it’s important to keep mundane-use items out of the shrine; the distinction helps the ritual-prone human brain understand that shrine is a special place and also helps keep your shrine orderly. Many pagans will include natural and found objects, such as leaves, flowers, pinecones, rocks, crystals, small twigs, sand, or soil; some pagans also include animal products, such as skins or furs, feathers, bones, or teeth. As mentioned earlier, many Kemetics follow ancient Egyptian standards for ritual purity for their shrines and will not use any animal products in shrine, up to and including wool, resin, and plastic.

By all means, use or exclude whatever feels true to you, and if you’re uncertain, check with Netjer or a particular deity to see if They mind the presence of a certain object. I am of the opinion that, if you use ethically-sourced materials (animal products or otherwise) and your gods are okay with it, there’s no problem. If you’re hesitant, you could easily draw the line between animal products that do not harm the animal (shed feathers or hairs) and products that might have or did harm the animal from whence they come (teeth, hides, and bones). I personally use resin statues (and a plastic lighter) on my main working shrine, and on the small shelf that is specifically Sekhmet’s, I have a rawhide cord with a couple (legally- and ethically-obtained) lion bones. I do keep blatant animal products off my “working” area, but don’t mind featuring them on other shelves in my shrine space.

It’s worth mentioning that all shrine items, including an altar cloth if you use one, should be kept physically clean—and it’s not a bad idea to regularly purify them, either energetically or symbolically. Natron and water are the typical choice for purification of a person or an object, and salt will do in a pinch; depending on the object, you can either wash it in water with a little natron in it or sprinkle it with dry natron (or salt). A spoken purification adds heka and power to the cleansing and is recommended—use an existing purification or make your own. My go-to is a simple fourfold repetition of “I am pure” or “it is pure.”

To sum up: a Kemetic shrine can be complex or simple, large or small, permanent or out-as-needed. Kemetics frequently use their shrines to pray, to make offerings, to perform heka, and to perform rituals, so items present should include an offering plate and cup, as well as the good ole standbys of candle and incense (or reasonable facsimiles, depending on living constraints). The shrine area can also feature icons or symbols of Netjer or particular Netjeru and should be kept clean and free of mundane items.

If you enjoyed this post, please check out the other takes on setting up a shrine by my fellow Round Table bloggers!

PBP Fridays: K is for Holy Kites

Birds served a variety of roles in Egyptian mythology; the Nile valley was rife with all sizes and shapes of wings. Flocks of migratory birds could lay waste to fields and orchards, consuming the crops, so netting swarms of birds in art or act could be symbolic of ma’at (rightness) conquering isfet (uncreation) or of ancient Egyptians defeating foreign invaders. Depictions of imprisoned enemies at Kom Ombo included captured flocks, and the swallow was a hieroglyph frequently used to write the names of undesirable things.

But Kemetic myths are also populated with solar hawks, maternal vultures, a wise ibis, and a great goose Who brought the world into being. The eternal soul, the ba, is shown as a human-headed bird. And, far from least, is the subject of today’s post: kites and the goddesses Who took on their form, Nebt-het (Nephthys) and Aset (Isis).

Nebt-het (left) and Aset (right)

Red kites, which are my best guess at the particular species of kite that Nebt-het and Aset are depicted as, are medium-sized raptors with forked tails and an amiability to both live prey (from rabbits to earthworms) and carrion. They have a high, thin cry, which relate them neatly to Nebt-het and Aset when They were mourning Wesir (Osiris), the dead god. In searching out Wesir’s body after He was killed, Aset was the one Who sought, and Nebt-het was the one Who found, aloft on swift wings with long-reaching eyes.

Red kites, which are my best guess at the particular species of kite that Nebt-het and Aset are depicted as, are medium-sized raptors with forked tails and an amiability to both live prey (from rabbits to earthworms) and carrion. They have a high, thin cry, which relate them neatly to Nebt-het and Aset when They were mourning Wesir (Osiris), the dead god. In searching out Wesir’s body after He was killed, Aset was the one Who sought, and Nebt-het was the one Who found, aloft on swift wings with long-reaching eyes.

So kites became symbols of grief, of loss—and of finding again. Wesir rose up when Nebt-het and Aset recovered His body and restored His limbs, and though He was never “alive” again, not like the rest of the Netjeru, He was not wholly undone and vanquished. Kites, with their shrill calls, took in both living and dead sustenance to survive, and so Nebt-het and Aset are Netjeru with a hand extended towards Their dead lord and the blessed dead that He caretakes… and a hand extended towards the living gods and we living mortals.

Sources:

- Egyptian Mythology (Geraldine Pinch)

- Nebt-het: Lady of the House (Tamara Siuda)

Last year’s first K post was on Khepri, Khepera, Kheperu.

the sine wave

My Wednesday-Friday post pattern significantly slipped for the first time since I set it in January. I have ideas for backdated posts and will fill them in as I find time, but the past few weeks have been busy and distracting with non-Kemetic life.

I’ve been reading the occasional book and making the occasional art. I’ve joined a new tabletop game with a few friends, which has proven to be hilariously fun. My job is always busy, and now I’ve added a few espresso shots of freelance work on top of it, as I periodically do. My partner’s mom stayed with us for half a week around Mother’s Day, and next week, my sister will come visit, which delights me to no end.

This is probably one of those natural fallow times I keep hearing (and occasionally writing) about. I haven’t done more than a couple shrine visits; I haven’t been writing litanies or prayers. I haven’t been studying or spending a lot of time thinking about Netjer and my gods. I’ve maintained my morning prayer and my akhu thank-yous when driving, but let slip anything larger.

But I am living in ma’at as best I may, and I am still in love with my path, and I am still deeply devoted to my gods.

This post can serve as a gentle reminder to come back up out of the mundane trough… and acceptance that this sine wave is natural, and okay, and not a failure on my part to be a superhumanly perfect Kemetic. :)

PBP Fridays: J is for Kemetic Jokes

This post will consist largely of modern Kemetic jokes, but for actual, researched, well-written articles on ancient Egyptian humor, check these out:

- Ancient Egyptian Humour on Reshafim

- Ancient Egyptian Humor (PDF) by Amr Kamel, Egyptologist, American University of Cairo.

And now, have some funnies!

Thank you, thank you, I’ll be here all week! ;)

Last year’s second J post was on sacred jewelry.

KRT: Heka

This post is part of the Kemetic Round Table, which aims to answer some of the most common questions and provide a wealth of diverse options for the Kemetic novice to explore.

Today’s Kemetic Round Table post covers heka; specifically, what it is and how it is used.

I would like to, first and foremost, direct your attention to two exemplary posts: the first by Sarduriur as a general academic overview of what heka is (and is not), and the second by Saryt as an interpretation of heka applied to music. They are both stellar reads and speak volumes beyond what I will cover here.

Furthermore, since I’ve already written my take on the basics of heka, I would like to give some examples of heka, rather than restate myself or repeat portions of the aforelinked fantastic essays.

To sum up briefly: Heka is not magic as Westerners think of magic; it is authoritative utterance or meaningful speech, and it is a power that lies within every person and every Netjeru. Heka is a natural and neutral tool, neither innately positive or negative, and can be used to defend and attack as well as propitiate and strengthen. Heka was frequently used to identify oneself with different deities in order to assume Their characteristics (and powers) and can be akin to sympathetic magic in that regard; to speak (or scribe) is to make it so.

Now, let’s get to a couple of modern heka samples, shall we? They should illustrate just how simple and clear-cut heka can be; it’s not all fancy ceremonial litanies that take half an hour to recite! (Not to knock long-form heka, mind; it has its place, as do the briefer kinds.)

first heka: for migraines

I suffer from migraines, and while I have them in hand for the most part, they can still take me out at the kneecaps if I’m caught unawares. Because a migraine feels like my brain is unraveling in a rather painful and messy fashion, I liken it to uncreation, and I invoke the Eye of Ra Who has made me to protect me. (In my particular case, the Eye can be both Nebt-het (Nephthys), my divine Mother, and Sekhmet.) While this heka could also be done by my directly assuming the role of the Eye goddess, I am usually too swamped by the migraine symptoms to confidently pull that off.

This migraine seeks to uncreate me!

Its darkness is the darkness of Apep‘s coils;

its pain is the pain of Apep‘s teeth.

My Lady the Eye burns away the shadows;

She burns away the pain and cauterizes me.

My Lady the Eye has created me

and no force shall undo Her work in me.

second heka: for eye trouble

I wear contacts, and on rare occasion, I’ll get some little grain of grit sandwiched between a lens and my eye. It’s deeply uncomfortable and often sharply painful, and since I don’t currently have glasses of an appropriate Rx, I’m stuck hoping I can wash the offending particle out and put my contact right back in. Given that I’d be legally blind without contacts, it’s kind of vital that I be able to wear ’em, especially at work or while driving. I’ve used the below heka a couple times to considerable effect; the first two lines are paraphrased from an ancient prayer to Bast-Ra.

Turn to me, peace-loving Netjer, forgive me;

Make light for me so I can see Your beauty.

My eye is the eye of Heru that was wounded and made whole again.

third heka: job-hunting

This heka was made for my partner, the first part to be spoken before starting a job-hunting session (online or in person) and the second part to conclude that session. I involve Heru-wer only because He’s willing, but other deities could easily take His place if the need arose.

Heru-wer, accept this incense and grant me opportunity.

My eyes are Your eyes, my hands Your talons;

I will swoop down and seize success.

. . .

Thank You for Your long sight and swift wings, Heru.

May we enjoy victory together – nekhtet!

fourth heka: protection

This is part of a longer execration heka; I conclude the heka by invoking my personal Netjeru (plus Set) for protection.

Nebt-het watches over me,

Hethert-Nut uplifts me,

Ma’ahes guards me,

Serqet guides me.

Sekhmet is over me,

Set is behind me,

Netjer is around me.

I am safe from all isfet.

If you enjoyed this post, please check out the other takes on heka by my fellow Round Table bloggers!